No, you can't bet on everything and that's okay

Prediction markets, despite their theoretical promise and success in sports ($330B US betting volume) and elections ($40B in 2024), are unlikely to become mainstream for all future events due to fundamental demand and liquidity constraints. The core issue isn’t regulation or technology - it’s that none of the three key market participants find prediction markets appealing: gamblers want quick resolutions (42% of 2020 election volume traded in final week), long-term investors prefer growing wealth in traditional assets, and market makers can’t operate without consistent retail flow (there is no demand for betting on topics except elections and sports).

This creates a structural chicken-and-egg problem where lack of demand and participations prevents reliable pricing, which in turn discourages serious folks. Due to these unfortunate structural issues, these markets only work in certain niches and in events with high public interest and pre-existing communities, immediate resolutions and natural gambling appeal.

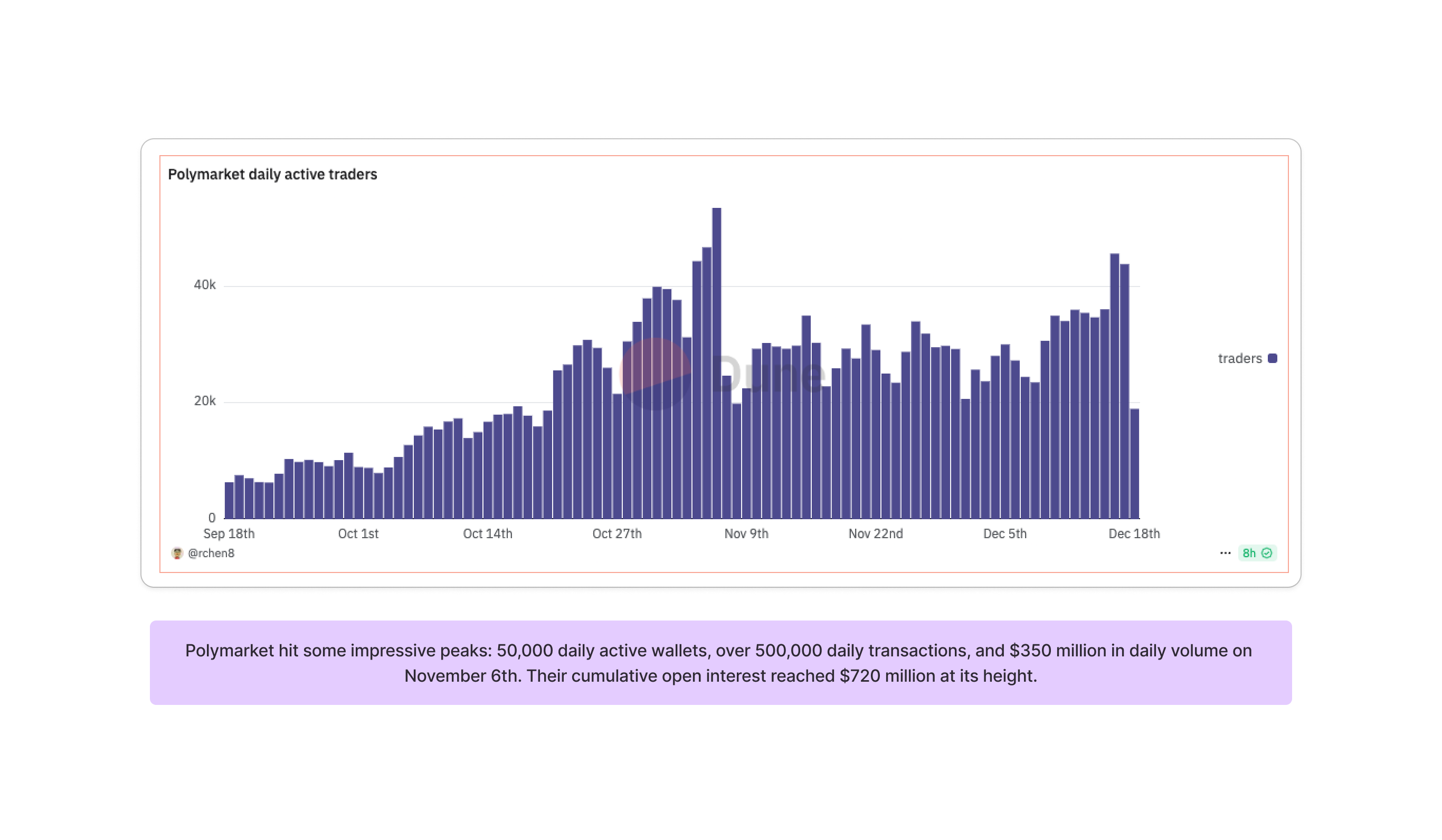

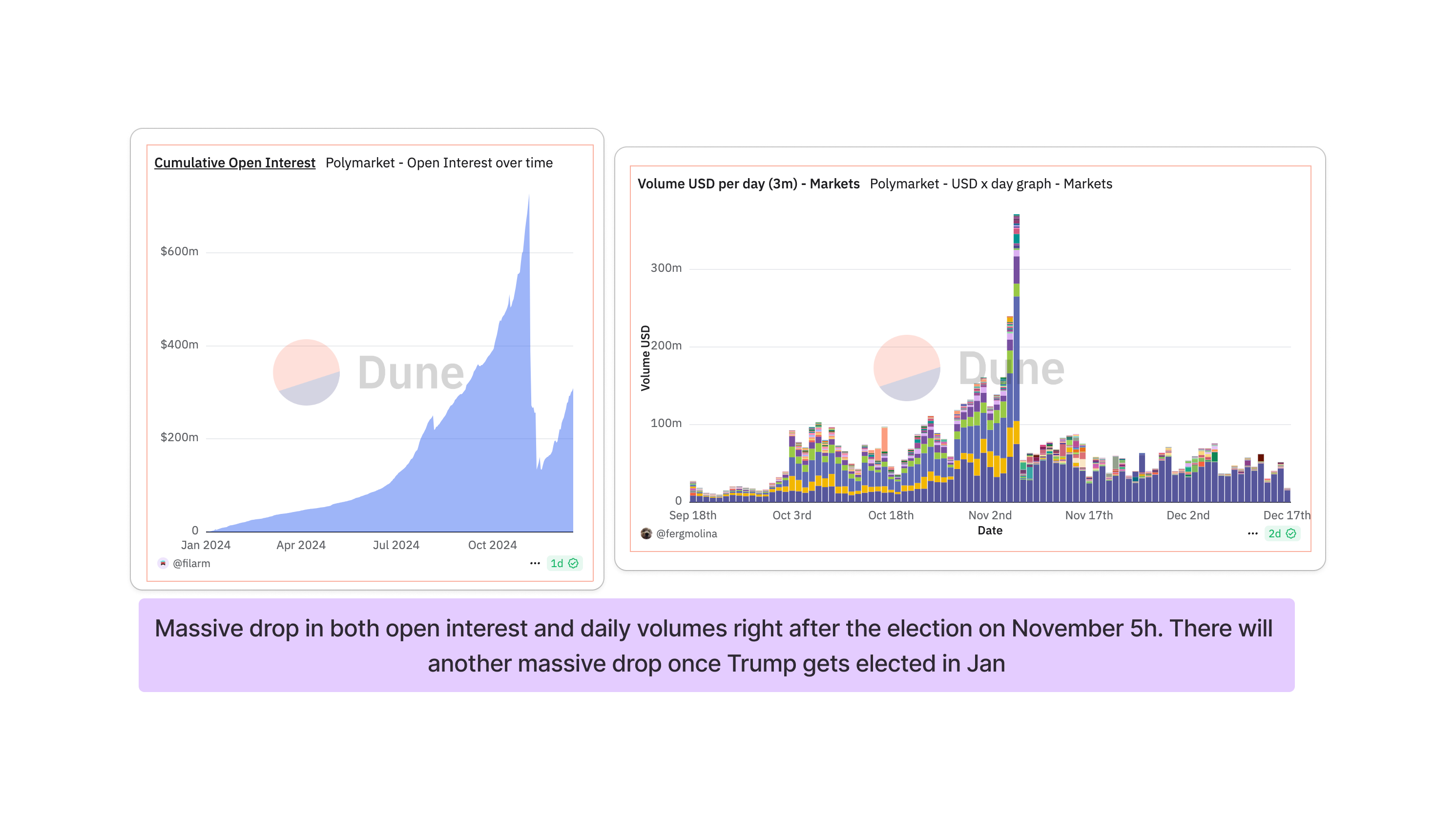

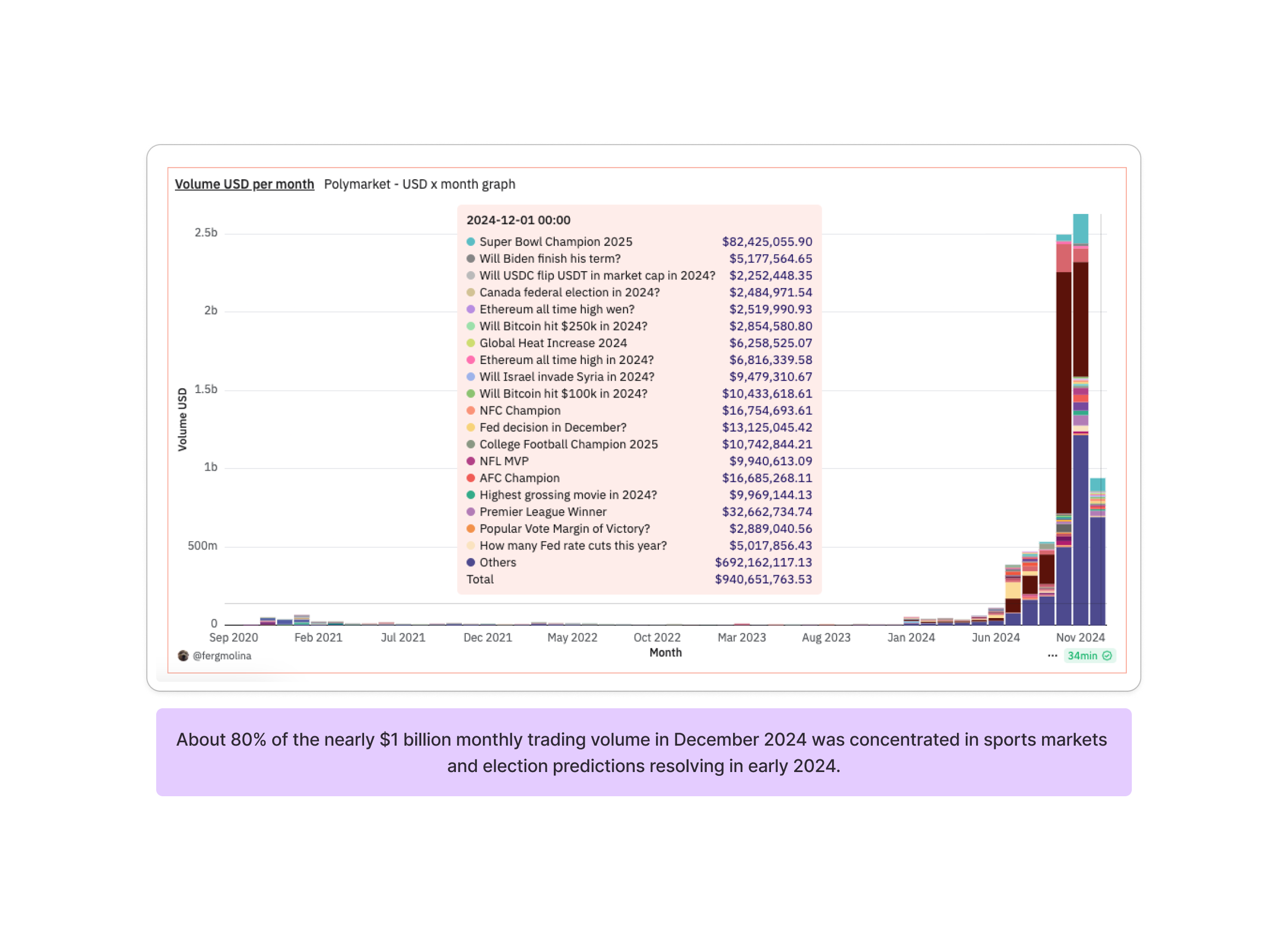

I’ve been using prediction markets for various purposes over the last couple years, from speculating on sports to more recently the US elections and the F1 season. These products are pretty popular. Americans legally bet over $330 billion on sports in 2023, while the 2024 US presidential elections saw about $40 billion in wagers. Polymarket alone saw over $2 billion in volume just in October 2024. Looking at this explosive growth, it’s easy to get excited about the future of prediction markets. Based on this Nick Whittaker inspired essay we investigate their hyposthesis along with data from on-chain.

This is the premise: harness the wisdom of crowds through financial incentives to predict future events. Put your money where your mouth is, and the market will aggregate everyone’s knowledge into probability estimates. At their core, prediction markets are betting markets where people can wager on the outcome of future events. The market price represents the crowd’s collective estimate. If shares are trading at $0.60, the market thinks there’s a 60% chance of that outcome happening. Curious about whether who is going to be the next NBA champion? There is a market for that. Wonder whether Tiktok will get banned in 2025 in US? There is a market for that. The dream is “prediction markets on everything”, where you are able to bet on every possible thing that can happen in the future.

But after diving deep into how these markets actually work and analyzing real usage data, I think I was wrong about their potential to become mainstream products. While they may excel in niches like sports and elections, they may not become ubiquitous. Even in places where regulations are favourable (Betfair and UK), prediction markets have been unable to grow in volume beyond some categories. The reality is more nuanced and the challenges more fundamental than people realize. Let me explain why.

How do prediction markets work?

Proponents(Vitalik calls it info finance) argue that prediction markets harness the “wisdom of crowds” and there are some famous examples of this working:

- In 1906, a crowd at a livestock exhibition collectively guessed an ox’s weight within 1% accuracy by averaging their estimates

- In 1968, the US Navy found a missing submarine using collective expert predictions that were just 220 yards off

The theory makes sense. Prediction markets get people to bring information into the open by effectively paying them for revealing it. The market aggregates all this information into a single price that represents the collective estimate of that event happening.

Prediction markets aren’t new though. Italian city-states had markets for papal elections in the 16th century. The US has had political betting markets since its founding. But what makes them powerful is how they incentivize information sharing. If you know something the market doesn’t, you can profit by betting and moving the price to reflect that information.

There was a lot of hype around Polymarket this cycle where people claimed that it was able to predict the results more accurately(and ahead in time) than the polls(and even mainstream media). This is because polls ask for “Who will you vote for?” whereas prediction markets ask “Who do you think will win?” with financial incentives for accurate predictions, regardless of personal preferences. These don’t align often because one is your personal perspective and another is your personal preference(or intent). This combined with possibility of hedging (I will bet on Harris as a hedge because my crypto bags will any go up if Trump gets elected) explains the divergence.

While there are different types of prediction markets (binary,continuous, etc) and different mechanisms to match the trades, most of the technical details are irrelevant to this particular blog. You can read more about prediction markets on this Lesswrong post or about order matching systems in this article. In practice, most successful prediction markets are hybrids. Polymarket, for instance, does order matching off-chain but settles everything on the blockchain. This gives you the best of both worlds - fast trading but transparent settlement.

One key thing to discuss here is about liquidity in prediction markets. When a new market is started, its generally not +EV for market makers to provide liquidity (unless such markets exist somewhere else and you have an idea of the probabilities) which means somebody has to subsidize or provide incentives for putting up the initial money. This is usually done by providing some sort of kickbacks or yield on the money which is locked up.

So, if the theory is sound, why am I not seeing prediction markets where I can bet on Bangalore weather?

The problem with Prediction Markets

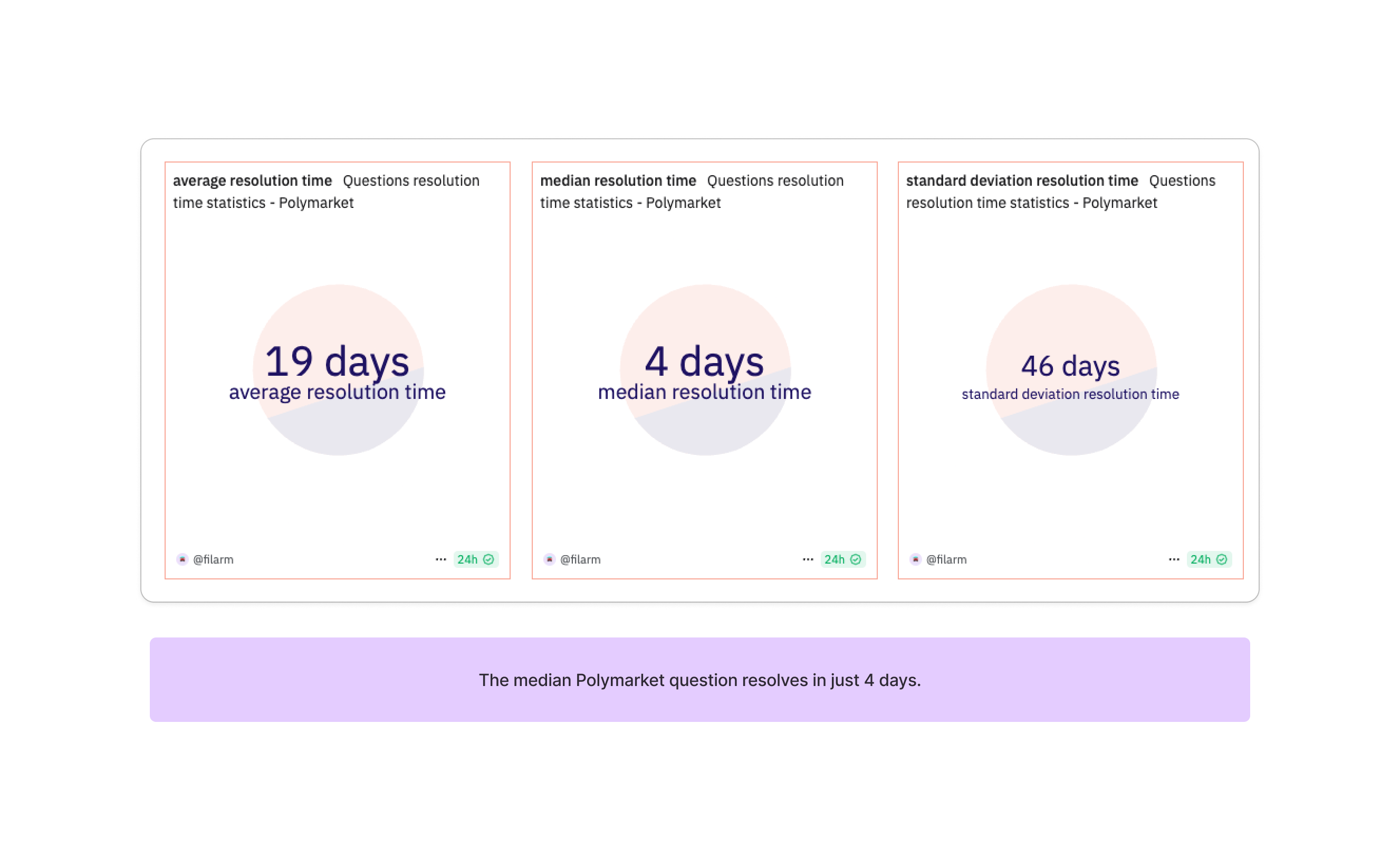

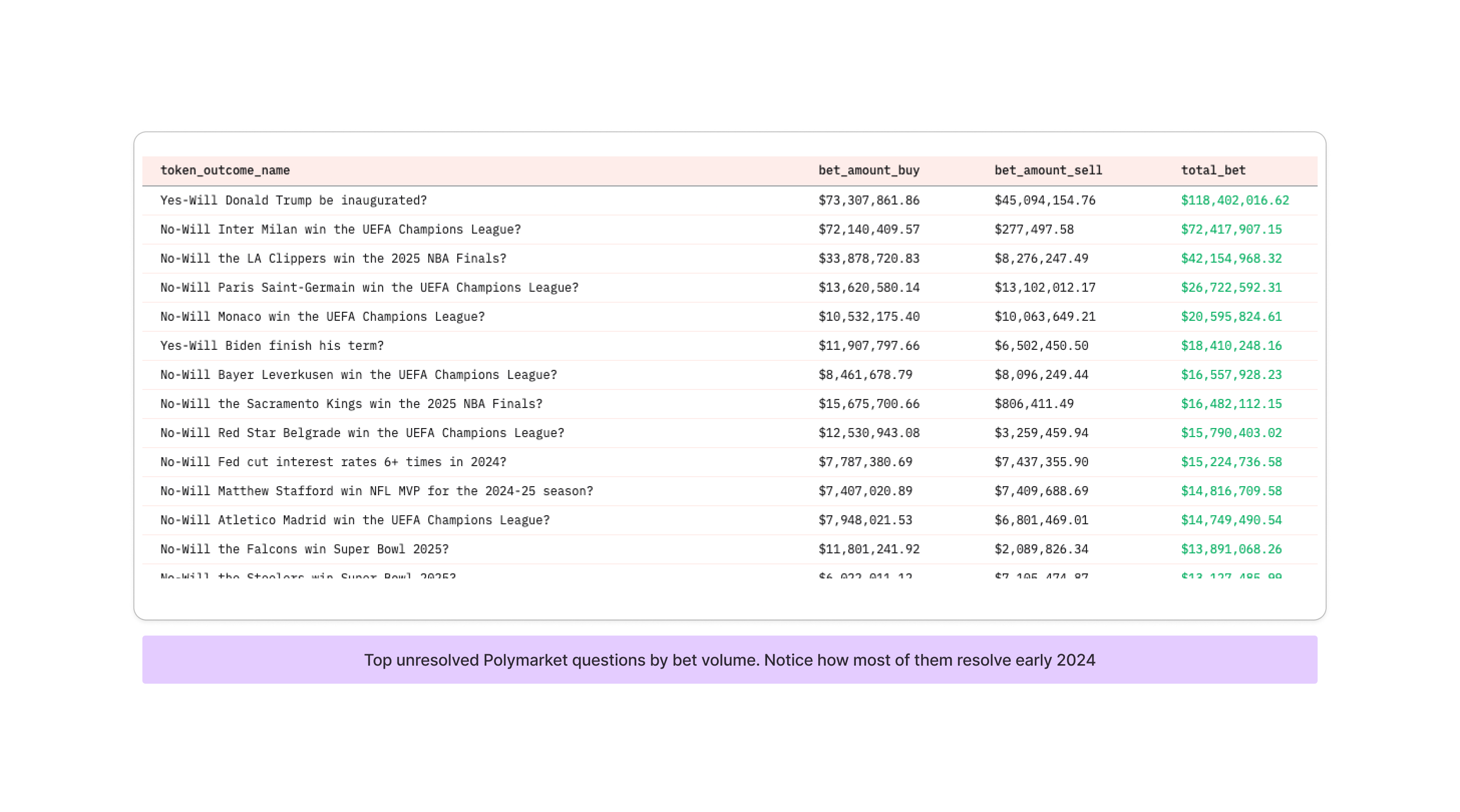

Despite their theoretical promise, prediction markets today face some limitations. The most obivous and repeating pattern is the crazy concentration of liquidity in short-term events and in certain niches. In India, crypto and cricket is responsible for about 80% of the volume on platforms like Probo, Winzo and MPL. On platforms like Polymarket, markets expiring within days or weeks see much higher trading volumes than longer-dated ones. This mirrors behavior in options markets, where short dated options have much higher OI compared to ones expiring next month.

Globally, volumes are dominated by elections and sports betting. The contrast becomes starker when looking at other types of markets like ones focused on scientific discoveries, CEO replacements, AI predictions, economic indicators, or technological developments. They often struggle to attract meaningful participation. Polymarket’s data shows this clearly - while their election markets saw daily volumes exceeding $350 million during peak periods, most other markets struggle to maintain consistent daily volumes above $1 million.

To understand why prediction markets struggle to scale beyond a few high-profile events, we need to look at the three key types of participants in any financial market:

Speculators/Gamblers: They’re in it for the thrill and don’t necessarily have an edge. Think retail options traders or meme coin enthusiasts. They generally make -EV bets. They usually bet on events which the general population is interested in. They prefer to have quick resolutions and not wait weeks/months for the bet to resolve

Long-term Investors: They’re trying to build wealth over time through appreciating assets like stocks. (Ex: an average SIP investor)

Market Makers/Sharks: The sophisticated players who provide liquidity and try to profit from pricing inefficiencies. (Ex: SIG, Jane street, etc) They usually make +EV bets and are very PnL consious

The problem? None of these groups find most prediction markets particularly appealing. Prediction markets have a major demand side problem

Why Current Prediction Markets Struggle

Let’s break it down by user type:

Speculators/Gamblers only care about quick resolution:

- Notice how 99% of prediction market volume happens right before the event. Majority of the Polymarket election betting volume was on October. Short dated options have way more volume than long dated options.

- They want immediate feedback loops and gratification

- Long-term predictions are boring for them

Long-term Investors have zero interest in locking up money in prediction markets because:

- The capital doesn’t generate returns while waiting for event resolution

- They can invest in stocks/bonds instead and actually grow their wealth

- This is why responsible people have their savings in stocks and real estate, rather than a diversified portfolio of sportsbooks

Market Makers/Sharks can’t operate effectively because:

- There’s not enough retail flow and liquidity to trade against and they don’t want to trade mostly against other professionals. It’s like showing up to a poker table and finding out all the other players are poker pros. You’d much rather have a table of tourists. In regular markets, there is a constant flow of long term investors wanting to grow their wealth.

- Counter point: Kalshi announced in April 2024 that Susquehanna International Group, a quantitative firm, had joined the platform as a market maker. But, in my view, markets are held back by the lack of long term investors and gamblers, rather than folks like SIG, Jane street, etc.

- Market size for 90% of the markets is too small to justify sophisticated analysis.

- Even these people don’t want to lock up the capital in long term bets because of the opportunity cost

This leads to a chicken/egg problem. Without gamblers and long term investors providing liquidity, market makers won’t participate. Without them making markets efficient, the prices aren’t reliable enough to attract serious investment. And 99% of the markets are too small to justify professionals spending time researching them. If people actually wanted to bet on random things, financial insitutions would have dumbed it down for retail customers (like they did with stock options, futures etc)

When Do Prediction Markets Actually Work?

Markets based on sports have some very nice qualities. They repeat predictably (lot of data points for market makers), are short-dated (conclude fast) and are generally very communal events with massive particiaption from the general public. This quick resolution is critical for attracting gamblers, who strongly prefer immediate results. Elections, while less frequent, generate similar dynamics because they attract massive public interest and thereby liquidity. The social element is crucial too. People are already fans of teams and political candidates, creating natural communities. This built-in audience provides the baseline liquidity for markets to function and scale up.

To put it simply, not enough people in the world care about random topics like whether the LK-99 superconductor paper can be replicated or whether we will make contact with aliens by 2030. I’ve intentionally ignored various subsidy mechanisms which bootstrap multiple prediction market contracts because they aren’t super relevant to the discussion.

To summarise, these markets they work when:

- Events resolve quickly (sports, short term politics)

- There’s massive public interest driving volume

- The underlying event recurs frequently enough to maintain engagement

So what now?

I think a general way these platforms wil grow is when they:

- Focus on niches with natural gambling appeal(massive public interest) and quick resolution.

- Improve the core betting mechanics and not get distracted by fancy formats (video interfaces, blockchain, etc.)

- Design for small, repeatable betting loops that maintain engagement. Micro betting(what happens in the next ball?) volumes are much bigger than full game outcomes (who will win this match?)

Prediction markets might be most valuable as an additional signal alongside other prediction methods, rather than trying to replace them entirely. They excel at aggregating information for events that people naturally want to bet on, and perhaps that’s exactly where they should stay. Not everything needs a prediction market - and that’s okay.