Counterfactual Regret Minimization or How I won any money in Poker?

As most readers of my blog would know by now, I used to play Poker for a couple years as a full time endeavour. One of the main tools we used for learning the game were called “solvers”. This blog post is about these programs and how they work? An introductory understanding of Poker terminologies, betting sequences and basic conditional probability is required for this post.

Background

A lot of games have been used in the AI domain like chess, checkers, Go and Poker. Games like Poker are special because of the key element of imperfect information. Unlike Chess and Go where you have the entire board in front of you, in Poker you don’t know your opponent hole cards. Its harder to come up with an optimal strategy of play when you don’t have the entire information and its more interesting because its similar to a lot of real world decision making settings. We will not get into the details of Poker but rather try to understand how this game is “solved”, the methodologies used and real world implications.

University of Alberta has a Poker research group and they have been working on solving the game before anybody else as far as I know. They were one of the earliest folks to build a Poker bot(called Loki) which could fold/call/raise based on effective hand strength. However, the earliest research in the field I could trace back was to this seminal paper by John Von Neumann called “Theory of Games and Economic Behavior” where they discuss the concept of expected utility linking it to rational decision making.

Game theory in Poker

What does it mean to “solve” a poker game? When you find a Nash Equilibrium strategy (aka GTO strategy) for the game it means that the game is “solved”. By definition, if both players are playing this strategy, then neither would want to change to a different strategy since neither could do better with any other strategy (assuming that the opponent’s strategy stays fixed). However, GTO strategy is not always the best way to play the game. While GTO ensures that you are un-exploitable, this doesn’t mean you will be winning the maximum money. The best response strategy is the one that maximally exploits the opponent by always performing the highest expected value play against their fixed strategy. In general, an exploitative strategy is one that exploits an opponent’s non-equilibrium play.

However, solvers have no idea what “Nash equilibrium” even means. So, how do they figure out the GTO play? At its core, solvers are simply EV-maximizing algorithms. Each agent in a solver represents a single player. That player a single goal of maximizing the money earned playing. The problem is the other agents play perfectly. When you force these agents to play against each other’s strategies, they iterate back and forth, exploiting each other’s strategies until they reach a point where neither can improve. This point is equilibrium which happens to be the Nash equilibrium we discussed above. GTO is achieved by making exploitative algorithms fight each other until neither can improve further.

Before we proceed further, we need to define, what is regret in Poker?

Regret

When you think of Regret in Poker, what is the first thing that comes to mind? Its usually us regretting calls or folds or bluffs which we did that didn’t work out (being results oriented here to explain the concept). On a very high level regret is defined as:

Regret = (EV of your action) - (EV of the strategy)

Regret is a measure of how well you could have done compared to some alternative. Phrased differently, what you would have done in some situation instead. Counterfactual regret is how much we regret not playing some strategy. For example, if we fold and find out that calling was a way better strategy, then we “regret” not calling. Mathematically it measures the gain or loss of taking some action compared to our overall strategy with that hand at that decision point.

Minimizing regret is the basis of all GTO algorithms.

The most well-known algorithm is called CFR – counterfactual regret minimization. In fact, my entire process of studying Poker is one big algorithm. I used to play 10k hands, take it to my coach, get it reviewed against “correct” strategy and try to play more optimal next time. My whole studying process was to minimize regret in a way.

A common way to analyze regret is the multi-armed bandit problem. The multi-armed bandit problem is a classic reinforcement learning problem that exemplifies the exploration–exploitation tradeoff dilemma. The setup is simple. You are a gambler sitting in front of a row of slot machines. Each machine can give out a positive or negative reward. How do you decide which machines to play, how many times to play each machine and in which order to play them? Bandits are a set of problems with repeated decisions and a fixed number of actions possible. This is related to reinforcement learning because the agent player updates its strategy based on what it learns from the feedback from the environment.

This reinforcement learning problem is related to Poker when played in the partial information setting. In the full information setting, the player can see the entire reward vector for each machine chosen and in the partial setting, sees only the reward that the machine has chosen for that particular play. There are multiple basic algorithms to attack this and a basic one is the greedy algo where you sample each machine once and then keep playing the machine with highest reward in sampling stage. There are other version of the greedy algo where you sometimes randomly explore another machine. The idea of usually picking the best arm and sometimes switching to a random one is the concept of exploration vs. exploitation. Think of this in the context of picking a travel destination or picking a restaurant. You are likely to get a very high “reward” by continuing to go to a favorite vacation spot or restaurant, but it’s also useful to explore other options that you could end up preferring.

Before we proceed further, we need to understand the concept called “Game Tree”.

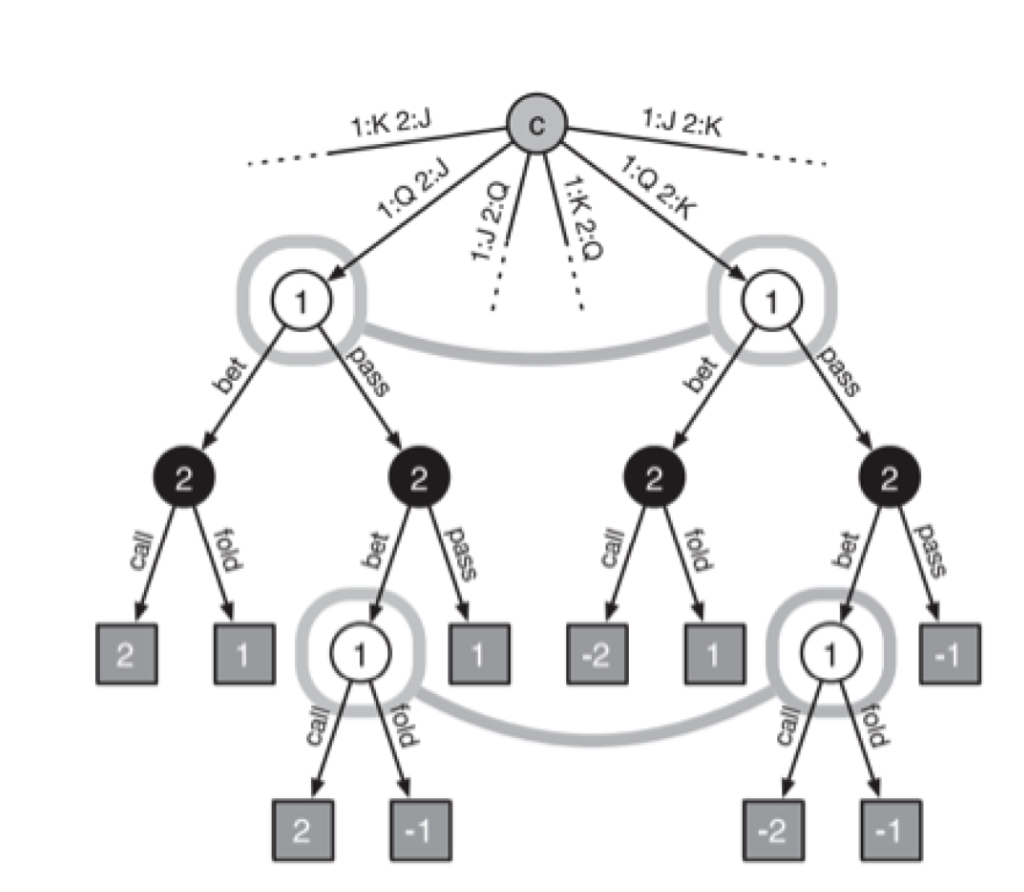

What is a game tree?

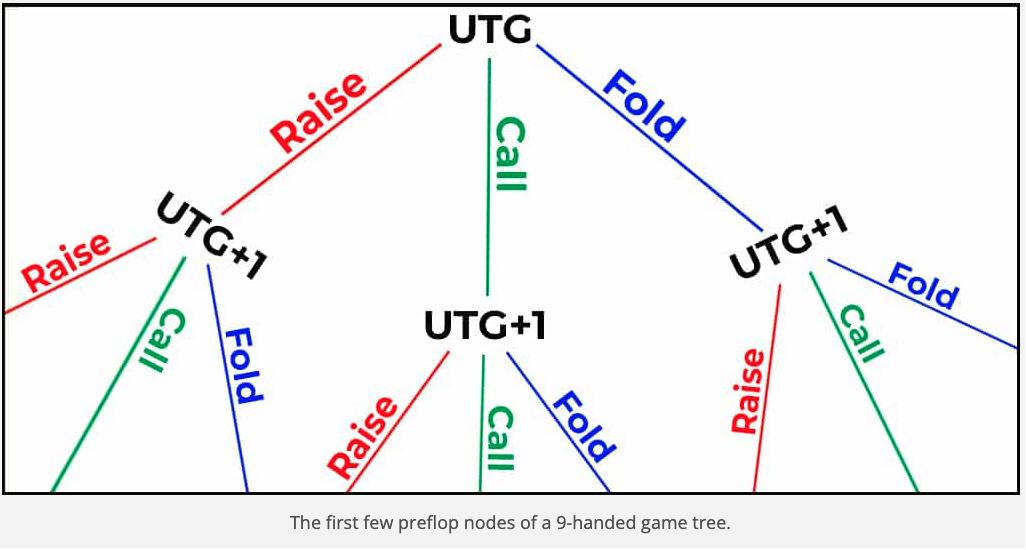

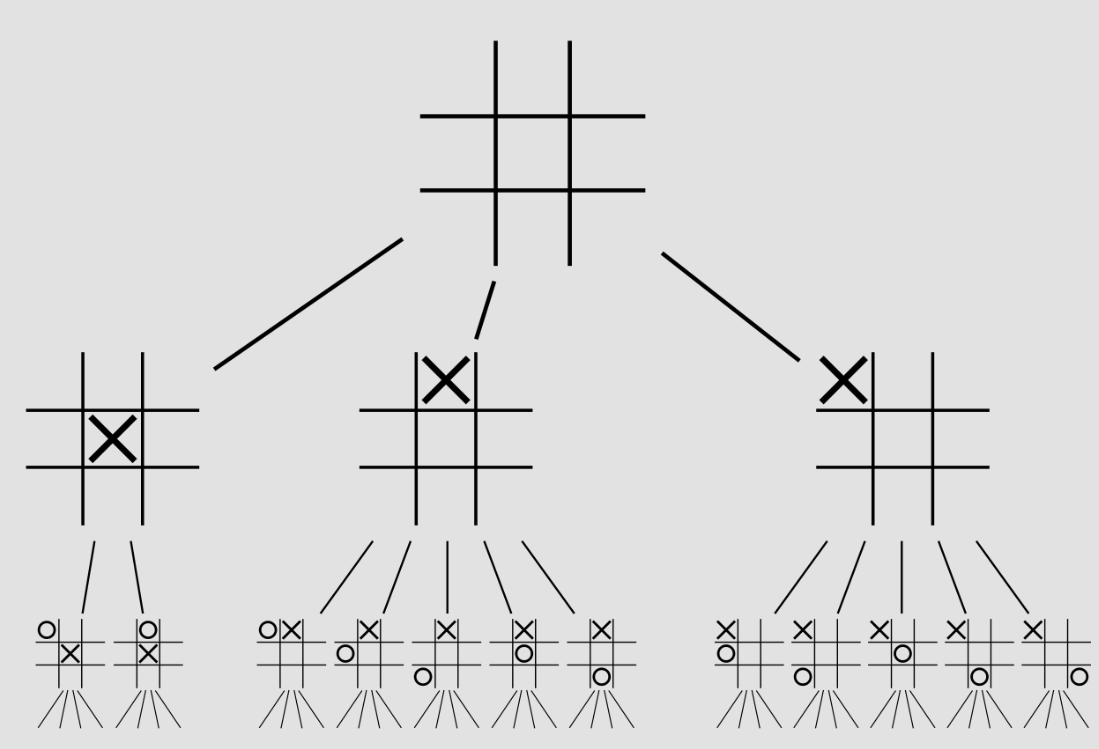

In the concept of sequential games, a game tree is nothing but a pictorial representation of every possible game state. This can be used to measure the complexity of a game, as it represents how dense and massive a game can play out over the long run. Below is an image of a game tree for ONLY the first two actions of the Tic tac toe game. The first player has three choices of move: in the center, at the edge, or in the corner. The second player has two choices for the reply if the first player played in the center, otherwise five choices. And so on. The number of leaf nodes in the complete game tree is the number of possible different ways the game can be played.

For example, the game tree for tic-tac-toe has 255,168 leaf nodes. In comparison, a super simplified, 2 player, limit hold-em has 1,179,000,604,565,715,751 nodes. Now, remember in a real world poker setting there are 6-9 players playing, with each having infinite number of bet sizes(limit hold-em example has just 2 bet sizes). This means the actual game tree of Poker is infinitely massive and we need smart algorithms to distill a GTO strategy from it because we can’t go the final leaf node of every strategy (computationally impossible). There are more leaf nodes than the number of atoms in the universe. As you will read later, the secret sauce of Pluribus comes from one such algorithm/approach. Two popular algorithms Minimax and Monte carlo tree search(MCTS) are some approaches that people take to find the optimal move through simulation. MCTS allows us to determine the best optimal move from a game state without having to expand the entire tree like we had to do in the minimax algorithm.

Apart from the Poker game tree being infinitely large, we have another problem. Poker is an imperfect information game but games like chess/tic tac toe are perfect information games. With perfect information, each player knows exactly what node/state he is in in the game tree. With imperfect information, there is uncertainty about the state of the game because the other player’s cards are unknown.

How to solve the game?

We have already defined what a “correct” strategy looks like and the game tree. At its core, we need to find the parts of the game tree which when played out gives us the maximum utility. I don’t want to make the post technical by talking about equities, probabilities and EV of every node but rather will keep things abstract for easier consumption.

- Step 1: Assign each player/agent an uniform random strategy(each action at each decision point is equally likely)

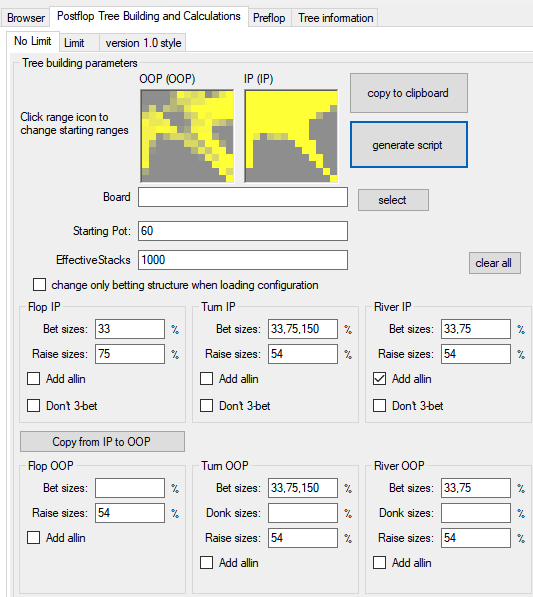

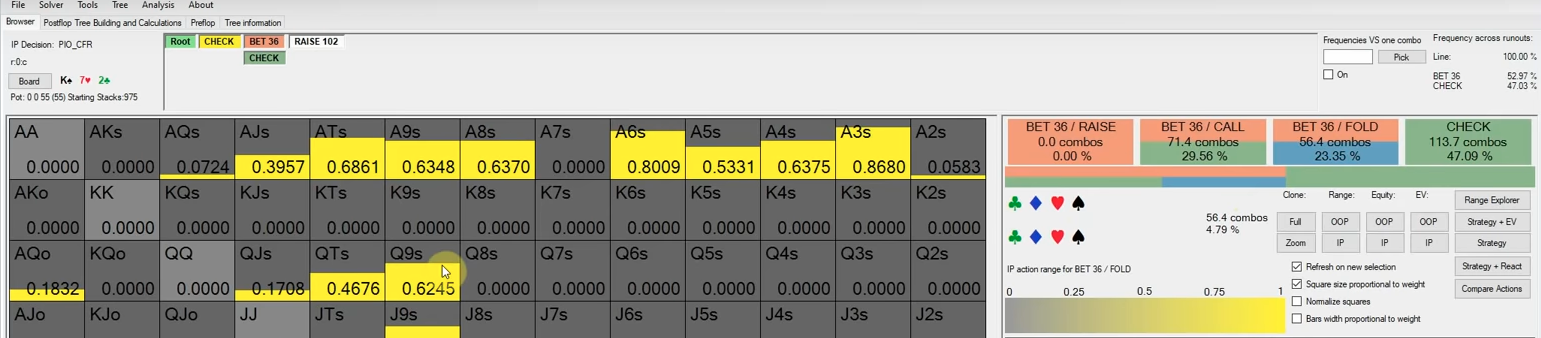

- This is the step where you define the game space. Things like the betting tree(you don’t solve ALL of poker in one go but rather in parts), required accuracy, starting pot values, stack sizes, board cards, starting ranges, any bucketing, rake, ICM are setup before the simulation starts. Remember, complexity grows our betting tree exponentially. If you want to solve 4-5x as many betting sizes, the tree would grow by 125x and becomes harder to solve. Funnily, this is still a major simplification of the true game space.

- One of the most difficult problems with solvers is optimizing betting trees to produce solid strategies within the constraints of current technology. We can only make a tree so big before it becomes unsolvable due to its size. We can only make a tree so small before the solver starts exploiting the limitations of that tree.

- Step 2: Compute the regret(EV loss against opponent move) for each action throughout the game tree

- While we have defined regret earlier, we need to exactly define what is the solver calculating here. In the previous step, we have defined the game space(and the leaf nodes we are interested in calculating) and here we calculate EV of each node. Its nothing but probability*value of the action.

- Step 3: Slightly change one player strategy (keeping opponent moves fixed) to reduce the regret calculated in previous step

- Once we have calculated the regret of our actions, how we figure out a new strategy. New Strategy = (Action Regret)/(Sum of positive regrets).

- Step 4: Repeat Steps 2 and 3 until you attain Nash equilibrium.

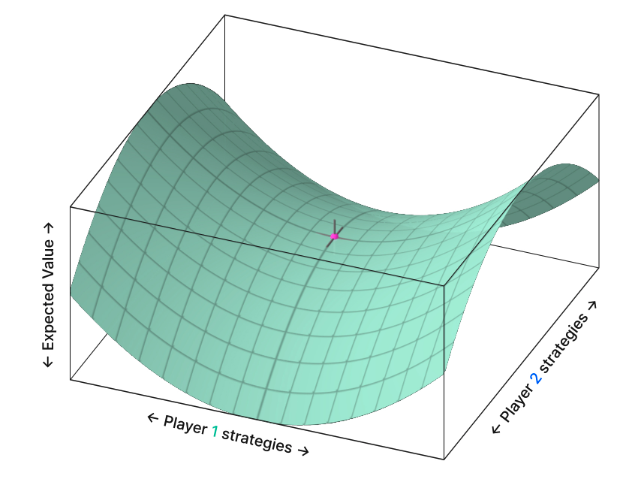

- I have already defined what Nash equilibrium is in Poker. But how do we know this is the most optimal part of the game tree? We certainly didn’t go through the entire game tree and instead took an iterative approach. What if we are stuck in a local maximum? What if going 100x pot size allin is the best strategy and we never iterated over it? Its impossible to know before hand what game space to iterate on. Poker, in general, can be described as a “bilinear saddle point problem”. The payoff space looks something like this:

- Each point on the x-axis and y-axis represents a strategy pair. Each strategy pair contains information about how both players play their entire range in every spot across every runout.

- The height (z-axis) represents the expected value of the strategy pair, with higher points representing an EV advantage for one player, and lower points representing a disadvantage

That’s it!. Almost all GTO solvers do the above 4 steps. They are aided with complex algorithms to simplify game trees, calculate regret faster, identifying which part of game tree is relevant. To ensure we aren’t stuck in a local maxima of the game tree, most solvers use a process called Counterfactual Regret Minimization (CFR). This algorithm was first published in a 2007 paper from the University of Alberta and it proves that the CFR algorithm will not get stuck at some local maximum, and given enough time, will reach equilibrium.

What is Counterfactual Regret Minimization (CFR)?

Counterfactual means “relating to or expressing what has not happened or is not the case”. For example, if in reality I drank 4 red bulls and couldn’t sleep in the night, I could say counterfactually, “If I hadn’t drank red bulls, I would have slept well in the night”. Regret we previously touched on is a way to assign a value to the difference between a made decision and an optimal decision. Minimization refers to minimizing the difference between the made decision and the optimal decision.

In the paper, they basically introduce the notion of counterfactual regret, which exploits the degree of incomplete information in an extensive game. They show how minimizing counterfactual regret minimizes overall regret, and therefore in self-play can be used to compute a Nash equilibrium. CFR is a self play algorithm that learns by playing against itself repeatedly. It starts play with a uniform random strategy (each action at each decision point is equally likely) and iterates on these strategies to nudge closer to the game theory optimal Nash equilibrium strategy as the self play continues (the average of all strategies converges to the equilibrium strategy)

The concept of counterfactual value calculation involves determining the values of actions within a game state by hypothesizing that we reach that state with a certainty of 100%. In this process, only the probabilities associated with the opponent’s and chance’s moves leading to that state are considered.

Counterfactual values are derived by multiplying the likelihood of the opponent and chance arriving at a particular state, the odds of progressing from that state to the game’s conclusion, and the final value at the game tree’s end. Within each information set of the game tree, the algorithm maintains a tally of regret values for each potential action. Regret here refers to the extent to which the agent would have performed better had it consistently chosen a particular action, instead of an average strategy comprising a blend of all actions. A positive regret suggests that an action should have been chosen more often, while a negative regret indicates that avoiding the action would have been preferable.

Minimizing regret involves favoring actions that perform better, thereby elevating the average value for the game state. The algorithm adjusts its strategy after each round to favor actions proportional to their past regrets. This means that an action with previous success is more likely to be chosen in the future. Proportional play prevents drastic strategy shifts, which could be predictable and exploitable. It also allows under performing strategies to potentially bounce back and be selected again.

The ultimate Nash equilibrium strategy, derived as an average of strategies across iterations, is deemed optimal. This strategy is expected not to incur losses and is theoretically sound, with neither player having a motive to deviate if both adopt an equilibrium strategy. This forms the basis of what is meant by “solving” a game like poker.

Reinforcement learning involves agents learning actions in an environment by considering past rewards, akin to the regret updates in Counterfactual Regret Minimization (CFR). Regrets in CFR resemble advantage functions, which compare the value of an action to a state’s value, as highlighted in recent studies like the Deep CFR paper. This concept parallels the idea of managing independent multiarm bandits at each decision point, learning from all simultaneously.

If CFR was invented long time back what was the breakthrough in 2019 which led to the building of Pluribus and the $1M prize game? They did Libratus first which was a 2 player version but a year later followed up with Pluribus which was a 6 player AI(exponentially harder to solve). The big breakthrough was the depth-limited search algorithm. This allowed them to shift a lot of the load from the blueprint computation to the online search algorithm, and the online search algorithm is relatively much more efficient. There were also advances in the blueprint computation itself, such as the use of linear CFR, but advances in the search algorithm were the biggest factor.

Where else is CFR useful?

Assuming Poker bots take over the online scene, where else can poker players and people building poker solvers get a job 🤣 ?

- Economic Modelling: CFR can be applied to model and analyze strategic interactions in markets, such as auctions and bargaining scenarios, where participants must make decisions with incomplete information about others’ strategies.

- Trading. Imagine a model which can show you ALL possible outcomes of the Russia-Ukraine conflicts impact on Oil prices and trade the highest EV stuff using that

- Decision support and negotiation: Running automated auctions(whats up crypto folks!), complex business strategy or even military planning

- Route optimization. Lot of the traffic routing algos use CFR and you can also model transportation logistics using this

Sources and Further reading:

- Libratus science.org

- Pluribus(elder brother of Libratus) wiki

- Pio Solver and Monker solver

- Reddit AMA from Noam Brown who is the father of this field

- Solving Imperfect-Information Games via Discounted Regret Minimization

- Using Neural networks to speed up CFR

- Maths of Poker

- CFR in Poker. First paper on this

- Deepstack by the Google folks

- How PhD people define all-in adjusted